A door is an idea made of wood

Steve Carr PGCE, MA(Psych)

steve@stevecarrtraining.com

We are never alone with our thoughts. Like male needs female to make baby, thoughts need a thinker before they can become an idea.

Thinking is a process by which thoughts occur and are processed by a ‘thinker’. There is either an internal or external stimulus followed by a response to the stimulus, a rationalising or categorising. Something else emerges between thought and thinker, something new. The stimulus is labelled, compared to prior knowledge and modified. Thoughts themselves may follow pattern but are often random, linked maybe, by a theme or chased down a sequential track.

A thought is like a lone spaceship of information looking for a planet to orbit and maybe land on. It is the thinker that gives the thought meaning and direction. The thinker clusters and thoughts together in patterns and associations and some thoughts naturally interest the thinker more than others. As an animal, a human is chiefly concerned with his own safety and survival. As such, thoughts that pertain more clearly to that survival arouse more curiosity in the thinker than others. As both an independent and interdependent creature, that survival is tied inexorably to others as they are both the source of danger and safety.

But it is not just this external relationship building that is important, it is the internal relationship that he builds between thought and thinker that will govern how he processes what emerges to stimulate his curiosity. In a way, all external objects are processed as thoughts. Other people are a collection of thoughts, stimuli, ideas, that must be processed. We can only understand the objectivity of another person by subjectively taking them apart and putting them back together internally. A door is an idea made of wood before it is a door.

The drive of the thinker is not for knowledge but for meaning. Knowledge, facts and theories are the tools of understanding; ways of understanding the world and our place in it. Knowledge of literature helps us understand more about ourselves, about love, about death about war about romance about history about people like us. It helps us understand our own place in the world, we test our preconceptions against characters or our families against other family constructs.

A baby has thoughts and feelings but has to develop ways of thinking about them. There is only a world of persistent sensations. It is through the relationship with the primary carer, someone NOT the baby that the baby begins to think about itself as an object separate from and different to another. It is this relationship that brings ‘objectivity’ to the developing mind. Further to this,it is the curiosity the infant has about the ‘mother’ that is the root of curiosity about an ‘other’ in the external world – including new ideas or new information or new people. And this curiosity is bonded for eternity in the instinct to get what the child and later the adult needs in order to survive.

A baby has thoughts and feelings but has to develop ways of thinking about them. There is only a world of persistent sensations. It is through the relationship with the primary carer, someone NOT the baby that the baby begins to think about itself as an object separate from and different to another. It is this relationship that brings ‘objectivity’ to the developing mind. Further to this,it is the curiosity the infant has about the ‘mother’ that is the root of curiosity about an ‘other’ in the external world – including new ideas or new information or new people. And this curiosity is bonded for eternity in the instinct to get what the child and later the adult needs in order to survive.

Working directly with the process and mechanism of this innate survival-linked curiosity is the basis of why and how we want to learn – anything!

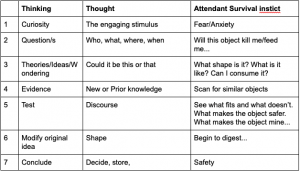

Coming up with a useful Formula/Template

So, like the babies that we remain, our first step towards acquiring understanding is coming across a stimulus that arouses our curiosity, a thought that crosses our path and from which we feel drawn to extract meaning and understanding. In a learning context, any new thought coming at us from the outside presents a threat because it is as yet ‘unknown’ and like an unknown person it may be dangerous. That is why we are driven to get to ‘know’ it. If we are able, we become ‘familiar’ with knowledge; know it like family. There is another question that is alive in this primordial soup of thoughts; if I conquer this ‘object’ will it feed me?

Curiosity breeds questions and a search for answers. If those answers can be found quickly then more the better for our desire for satisfaction and our threatened sense of safety. However, whether it takes a millisecond or a month of hard study, the process is the same.

Curiosity breeds questions and a search for answers. If those answers can be found quickly then more the better for our desire for satisfaction and our threatened sense of safety. However, whether it takes a millisecond or a month of hard study, the process is the same.

With curiosity comes questions, with questions come a search for answers. Initially these answers are put forward in theories and ideas, wondering whether it’s this or that, a or b. From wondering comes the desire to prove, so we look for evidence for our theories – in past experiences, other pieces of knowledge that might help. We then weigh that up, rationalise, formulate and maybe modify our initial thoughts and ideas before coming to a conclusion. What arrives with a conclusion is either a new sense of safety, the unknown monster has been slain, or a new question to which we may need to rise to and seek peace with.

The Magic 7 Learning sequence that follows this pattern.

So, does this work when we apply it to a particular subject area?

Shakesepare’s a Monster

Let’s take Shakespeare as an example. Shakespeare as a subject comes across the radar of a pupil in secondary school. Remember that we are naturally curious so whatever floats across our field of attention, we will be curious about it. The question is whether we are curious enough about it.

SHAKESPEARE – new thought with its associations of the unknown so anxiety is induced.

SHAKESPEARE – new thought with its associations of the unknown so anxiety is induced.

- Curiosity aroused and

- Questions emerge:

- What does Shakespeare mean to me, what can I get out of it?

- Is it going to be useful to me?

- Will it kill me/feed me?

3. Formulate theories and ideas:

- “I might get to understand what all the fuss is about?”

- “I might get to feel smart”

[Prior knowledge of “Shakespeare” gives rise to tangential awareness that there is a lot of ‘fuss’ about Shakespeare and that culturally people who know about Shakespeare are ‘smart’ people]

- Evidence:

This may be enough for the student look for or be led to the Evidence stage where they encounter Shakespeare in a way that helps them make an initial evaluation of whether they will get what they want from the subject.

- Test/Discourse

They might then turn that evidence over in their mind and through what presents as an internal discourse, testing against other internal criteria applying possible areas of growth…chewing it over and as such…

- Modify their ideas about Shakespeare.

- Conclude:

They then will naturally want to alleviate their anxiety and return to a place of knowing so will quickly come to a conclusion about Shakespeare.

Magic 7 Essay Plans

It’s no surprise that this process of overcoming and consuming the threatening object – in our case Shakespeare, maps very easily onto classic Essay Plans. Indeed, following the Magic 7 leads us through the way we learn and share meaning with one another.

Magic 7 Lesson plans too roughly follow this formula:

Magic 7 Lesson plans too roughly follow this formula:

- Create Curiosity through the subject/Aim of the lesson/statement.

- Allow the Aim to raise questions and set out how you are going to help answer those questions.What will we understand when we know x?

- Bring in prior knowledge and/or new knowledge and get students ‘wondering’, debating, discussing

- Show evidence for certain ways of looking at x or get them to find evidence that will satisfy their ‘wondering’.

- Consolidate through testing against other knowledge or ideas from other sources

- Begin to come to conclusions, modify initial thinking. What have we learned?

- Conclude…[and bring in another question]

In all of our learning we are the centre of the narrative

Whatever we are studying or we are always telling or retelling the story of ourselves in relation to others. Those others may be people but they are, more often, the “other” that is outside of ourselves. This could be knowledge and understanding of Shakeseare’s Tragedies as much as the guy who has moved in downstairs. We enter into a personal relationship with objects as much as we do loved ones, moreso because learning is full of others we do not yet know.

Whatever we are studying or we are always telling or retelling the story of ourselves in relation to others. Those others may be people but they are, more often, the “other” that is outside of ourselves. This could be knowledge and understanding of Shakeseare’s Tragedies as much as the guy who has moved in downstairs. We enter into a personal relationship with objects as much as we do loved ones, moreso because learning is full of others we do not yet know.

In this context, Poetry may present itself as a tricky character, difficult to fathom, full of double meaning, unwilling to reveal themselves fully, ready to humiliate and shame. Our curiosity for Poetry may be dampened by the prior knowledge of the intrinsic of danger this subject. From this perspective, poetry will not be conquered and consumed. Rather it will kill and consume.

So, poetry does not just exist in isolation as a subject. Students must be able to form a relationship with poetry, to tame it perhaps and make it safe enough, to come to ‘know’ it as they might a neighbour in class.

More important than what we might learn about poetry in an English class is what we will learn about ourselves, for better or worse. As with any subject we may find out what we don’t know. Rather than filling a hole in our understanding we are as likely to uncover one, maybe more than one. Our ideas about ourselves will be challenged, our identity and sense of who we are is on the line.

To learn effectively we need to feel safe enough to make a connection to what we are being taught and we need to feel the learning as a rich and useful food that will strengthen us or make us more powerful or offer us more internal resources that we can use on our journey. Thinking offers us ways of ordering our random thoughts into more meaningful and cohesive narratives. We are forever trying to use education to help us grow, to understand more about ourselves and the world. By thinking we invent a narrative for ourselves that helps us reflect not just on the ‘story’ but on the meaning of the story of our lives.

Steve Carr PGCE, MA(Psych)

Learning Teacher

References

Bowlby John A Secure Base Routeledge

Bion, W Experiences in Groups, Routeledge, London, 1962

Bateman. A. Homes. J Introduction to Psychoanalysis London, Routeledge, London1995

Freud S The dynamics of Transference, in J Strachey (Ed) (1953-56)

Klein M Our adult world and its roots in infancy. London, 1959

Klein M Envy and Gratitude 1946-1963 , The Hogarth Press, London 1975

Obholtzer, A. The Unconscious at Work, Routeledge, London, 1994

Saltzerberger-Wittenberg. Emotional Aspects of Learning and Teaching, Tavistock Publications, 2009

Waddel M, Inside Lives, Tavistock Clinic Series, London, 2007

Winnicott D. W Playing and Reality, Tavistock Publications, 1971

Youell B The Learning Relationship ,Karnac, London 2006