…once I got my mind right, everything else began to fall into place.

Child Psychologist, Donald Winnicott said “we have to recognise the everlasting in the ephemeral”. (Winnicott, 1971) In other words, don’t just react to the moment. When a child is off task and demanding attention by acting out, try to respond to the bigger picture, don’t just react to the moment. Easier said than done of course when that behavior has you emotionally backed into a corner and the rest of the class are waiting for your next move.

Control versus Contain

We have discussed how it is important for a child to be ‘held’ and we understand that a child who is held feels ‘contained’. He feels safe because whatever he is feeling is manageable; the grown up can deal with it, the grown up can “hold” it for them and with them. It’s important to realise that whatever feelings are being thrown at you in that moment are feelings that cannot be contained by the child in front of you and, as such, they feel most threatening, not to you, but to them. In other words, the anger they are showing is a result of their own inner sense of uncontainable chaos. They feel out of control and it’s frightening them. That’s why they are trying to get rid of it and give that feeling to you. The test is whether you can handle it.

We have discussed how it is important for a child to be ‘held’ and we understand that a child who is held feels ‘contained’. He feels safe because whatever he is feeling is manageable; the grown up can deal with it, the grown up can “hold” it for them and with them. It’s important to realise that whatever feelings are being thrown at you in that moment are feelings that cannot be contained by the child in front of you and, as such, they feel most threatening, not to you, but to them. In other words, the anger they are showing is a result of their own inner sense of uncontainable chaos. They feel out of control and it’s frightening them. That’s why they are trying to get rid of it and give that feeling to you. The test is whether you can handle it.

Recognising the anxieties that are present whilst not letting them overwhelm the individual student or spread to the rest of the class is key to developing consistent and effective classroom culture.

If you can respond to it in a way that shows that you are not afraid and demonstrate that you can help them “step outside of it”, . As a teacher, your role is to help these adolescents engage with, think about and take responsibility for their own learning. They need to be helped to feel the fear that learning evokes and keep moving forward. This is known as ‘containment’. The feelings are being ‘contained’ within the child or within the safety of the relationship with the teacher.

Recognising the anxieties that are present whilst not letting them overwhelm the individual student or spread to the rest of the class is key to developing consistent and effective classroom culture.

Containment demands a particular quality of attention, particularly in the early days with a new class. No two classes are ever alike. That’s part of the joy of teaching. It’s dynamic. Because no two classes are alike, you will need to slightly alter your approach with each of them. Remembering that all students want to be treated warmly and held securely – by a teacher who is consistent but not robotic – is the root of effective containment.

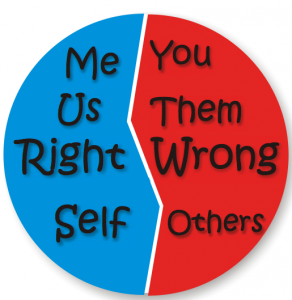

When I try to ‘control’ a class, I do it for my sake. I do it because I feel as though I can’t cope with them being ‘out of control’. There is an assumption that if I do not control them chaos will ensue. It is assumed that they will not want to learn if I do not control them long enough to force some knowledge down their throats.

The image that comes to mind is of holding a baby down long enough to feed it. But, of course, you don’t have to hold a baby down to feed it. A baby wants to attach, a baby wants to be held and have its anxieties contained, a baby wants to fed.

The image that comes to mind is of holding a baby down long enough to feed it. But, of course, you don’t have to hold a baby down to feed it. A baby wants to attach, a baby wants to be held and have its anxieties contained, a baby wants to fed.

If we really want to be effective teachers we need to realise that what any pupil wants, what any class wants from a teacher is not to be controlled but to be contained; to feel safe enough to take the learning that is on offer.

Students actively want your help, they just have a confusing way of asking for it.

We have already discovered that every child wants to learn. It is a natural instinct. This discovery had a profound effect o n my teaching practice.

n my teaching practice.

Because every child wants to learn, it relieves me of forcing them to listen. If they want me to contain them and make them feel safe, why am shooting myself in the foot by ‘going into battle’ with them. Students actively want my help, they just have a confusing way of asking for it.

If I want to be there and I show them that. If I really know that what they actually want is what I have to offer then the job becomes not about suppressing or controlling and censoring but about creating, including, guiding and setting clear boundaries. It’s what they want! It’s what we all want!

offer then the job becomes not about suppressing or controlling and censoring but about creating, including, guiding and setting clear boundaries. It’s what they want! It’s what we all want!

The Desire to Control Kills Creativity

My desire to ‘control’ my classes led to me shouting at them and setting tasks which meant they would stay in my control. Or, when I failed to control them, I would retreat and do the minimum in order to survive.

In practical terms, this meant setting work that was very teacher led rather than any group work or independent learning. It meant that I prepared for classes emotionally by stiffening up, by withdrawing and waiting ‘for battle’. I was, before the lesson had even begun, desperate for it to be over.

By trying to control a class I was giving them the message that I felt out of control.

Accepting that the pupils actually wanted to be contained meant that my sanctions or boundaries were not about me but about them. The moment I started to implement rules and boundaries because that was what they really wanted, the atmosphere in the classes I taught changed. Instead of getting the message that I was trying to control them because I felt I was out of control, they got the message that I was looking after them. This created an US mentality. We were in this together.

Accepting that the pupils actually wanted to be contained meant that my sanctions or boundaries were not about me but about them.

This is not a magic wand process.

It takes the persistence to show that you mean it, that you do want the best for them and that you are willing to do whatever you can to help them. It’s colloquial to say but once I got my ‘mind’ right, everything else began to fall into place. My classroom management problems were not over but I had a clear frame of reference that made the behaviour make sense to me and when I applied my learning to the situation, it nearly always worked!

It takes the persistence to show that you mean it, that you do want the best for them and that you are willing to do whatever you can to help them. It’s colloquial to say but once I got my ‘mind’ right, everything else began to fall into place. My classroom management problems were not over but I had a clear frame of reference that made the behaviour make sense to me and when I applied my learning to the situation, it nearly always worked!

Case study…8U

8 U were described as “out of control” by those who taught them. At the beginning of the year I spent the time leading up to teaching them in a state of high anxiety. What if I couldn’t control them? What would happen? How would I get through the hour? I can now see that these anxieties were probably being felt by the pupils also. “What will we do if he can’t control us?”, “What will happen?”, “How will we get through the hour?”. My anxieties overrode anything I had in mind about teaching them. The class became about my survival and I suspect it was similar for them.

However, once I realised that my role was to contain their anxieties, to create a safe place for them, I was able to attack the job with more clarity. I separated the desks and gave them less opportunity to disrupt one another and share their anxieties through collective misbehavior. I sat more challenging pupils closer to me (these were pupils who were struggling academically, so no wonder they wanted to disrupt the lessons). I laid out what we would learn at the beginning of the lesson and set a minimum that we needed to achieve. In other words, I was showing the class that I was ready and able to help them cope with their anxieties, and that I was able to cope with mine. This meant that we could all relax a little and get on with learning.

Winnocott says confrontation, “belongs to containment that is non retaliatory, without vindictiveness, but having its own strength”.

My need to contain rather than control never made me less of an authority in the classroom. If anything, I finally understood what rules are for and ho to apply them in the service of containment rather than control. I became less shy of confrontation because sometimes confrontation is absolutely necessary. Winnocott says confrontation, “belongs to containment that is non retaliatory, without vindictiveness, but having its own strength”. (1971) The knowledge that I am, as far as I am aware, not being vindictive but that I am trying to confront unproductive behavior in a strong way because it is the right thing for everyone, has been a significant development in my understanding of the learning relationship. It was simple yet seismic.